Transportation theory

In mathematics and economics, transportation theory is a name given to the study of optimal transportation and allocation of resources.

The problem was formalized by the French mathematician Gaspard Monge in 1781.[1]

In the 1920s A.N. Tolstoi was one of the first to study the transportation problem mathematically. In 1930, in the collection Transportation Planning Volume I for the National Commissariat of Transportation of the Soviet Union, he published a paper "Methods of Finding the Minimal Kilometrage in Cargo-transportation in space".[2][3]

Major advances were made in the field during World War II by the Soviet/Russian mathematician and economist Leonid Kantorovich.[4] Consequently, the problem as it is stated is sometimes known as the Monge–Kantorovich transportation problem.

Contents |

Motivation

Mines and factories

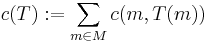

Suppose that we have a collection of n mines mining iron ore, and a collection of n factories which consume the iron ore that the mines produce. Suppose for the sake of argument that these mines and factories form two disjoint subsets M and F of the Euclidean plane R2. Suppose also that we have a cost function c : R2 × R2 → [0, ∞), so that c(x, y) is the cost of transporting one shipment of iron from x to y. For simplicity, we ignore the time taken to do the transporting. We also assume that each mine can supply only one factory (no splitting of shipments) and that each factory requires precisely one shipment to be in operation (factories cannot work at half- or double-capacity). Having made the above assumptions, a transport plan is a bijection  — i.e. an arrangement whereby each mine

— i.e. an arrangement whereby each mine  supplies precisely one factory

supplies precisely one factory  . We wish to find the optimal transport plan, the plan

. We wish to find the optimal transport plan, the plan  whose total cost

whose total cost

is the least of all possible transport plans from  to

to  . This motivating special case of the transportation problem is in fact an instance of the assignment problem.

. This motivating special case of the transportation problem is in fact an instance of the assignment problem.

Moving books: the importance of the cost function

The following simple example illustrates the importance of the cost function in determining the optimal transport plan. Suppose that we have n books of equal width on a shelf (the real line), arranged in a single contiguous block. We wish to rearrange them into another contiguous block, but shifted one book-width to the right. Two obvious candidates for the optimal transport plan present themselves:

- move all n books one book-width to the right; ("many small moves")

- move the left-most book n book-widths to the right and leave all other books fixed. ("one big move")

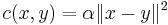

If the cost function is proportional to Euclidean distance (c(x, y) = α |x − y|) then these two candidates are both optimal. If, on the other hand, we choose the strictly convex cost function proportional to the square of Euclidean distance ( ), then the "many small moves" option becomes the unique minimizer.

), then the "many small moves" option becomes the unique minimizer.

Interestingly, while mathematicians prefer to work with convex cost functions, economists prefer concave ones. The intuitive justification for this is that once goods have been loaded on to, say, a goods train, transporting the goods 200 kilometres costs much less than twice what it would cost to transport them 100 kilometres. Concave cost functions represent this economy of scale.

Abstract formulation of the problem

Monge and Kantorovich formulations

The transportation problem as it is stated in modern or more technical literature looks somewhat different because of the development of Riemannian geometry and measure theory. The mines-factories example, simple as it is, is a useful reference point when thinking of the abstract case. In this setting, we allow the possibility that we may not wish to keep all mines and factories open for business, and allow mines to supply more than one factory, and factories to accept iron from more than one mine.

Let  and

and  be two separable metric spaces such that any probability measure on

be two separable metric spaces such that any probability measure on  (or

(or  ) is a Radon measure (i.e. they are Radon spaces). Let

) is a Radon measure (i.e. they are Radon spaces). Let ![c�: X \times Y \to [0, %2B \infty]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/7fba06fe2eb0ef7616086d36d9919601.png) be a Borel-measurable function. Given probability measures

be a Borel-measurable function. Given probability measures  on

on  and

and  on

on  , Monge's formulation of the optimal transportation problem is to find a transport map

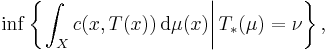

, Monge's formulation of the optimal transportation problem is to find a transport map  that realizes the infimum

that realizes the infimum

where  denotes the push forward of

denotes the push forward of  by

by  . A map

. A map  that attains this infimum (i.e. makes it a minimum instead of an infimum) is called an "optimal transport map".

that attains this infimum (i.e. makes it a minimum instead of an infimum) is called an "optimal transport map".

Monge's formulation of the optimal transportation problem can be ill-posed, because sometimes there is no  satisfying

satisfying  : this happens, for example, when

: this happens, for example, when  is a Dirac measure but

is a Dirac measure but  is not).

is not).

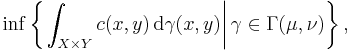

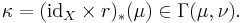

We can improve on this by adopting Kantorovich's formulation of the optimal transportation problem, which is to find a probability measure  on

on  that attains the infimum

that attains the infimum

where  denotes the collection of all probability measures on

denotes the collection of all probability measures on  with marginals

with marginals  on

on  and

and  on

on  . It can be shown[5] that a minimizer for this problem always exists when the cost function

. It can be shown[5] that a minimizer for this problem always exists when the cost function  is lower semi-continuous and

is lower semi-continuous and  is a tight collection of measures (which is guaranteed for Radon spaces

is a tight collection of measures (which is guaranteed for Radon spaces  and

and  ). (Compare this formulation with the definition of the Wasserstein metric

). (Compare this formulation with the definition of the Wasserstein metric  on the space of probability measures.)

on the space of probability measures.)

Duality formula

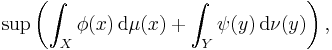

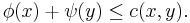

The minimum of the Kantorovich problem is equal to

where the supremum runs over all pairs of bounded and continuous functions  and

and  such that

such that

Solution of the problem

Optimal transportation on the real line

For  , let

, let  denote the collection of probability measures on

denote the collection of probability measures on  that have finite

that have finite  th moment. Let

th moment. Let  and let

and let  , where

, where  is a convex function.

is a convex function.

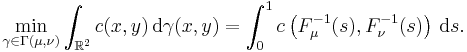

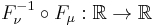

- If

has no atom, i.e., if the cumulative distribution function

has no atom, i.e., if the cumulative distribution function ![F_{\mu}�: \mathbb{R} \to [0, 1]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/fa78819db93cefa942d402802e23b95f.png) of

of  is a continuous function, then

is a continuous function, then  is an optimal transport map. It is the unique optimal transport map if

is an optimal transport map. It is the unique optimal transport map if  is strictly convex.

is strictly convex. - We have

Separable Hilbert spaces

Let  be a separable Hilbert space. Let

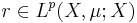

be a separable Hilbert space. Let  denote the collection of probability measures on

denote the collection of probability measures on  such that have finite

such that have finite  th moment; let

th moment; let  denote those elements

denote those elements  that are Gaussian regular: if

that are Gaussian regular: if  is any strictly positive Gaussian measure on

is any strictly positive Gaussian measure on  and

and  , then

, then  also.

also.

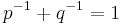

Let  ,

,  ,

,  for

for  ,

,  . Then the Kantorovich problem has a unique solution

. Then the Kantorovich problem has a unique solution  , and this solution is induced by an optimal transport map: i.e., there exists a Borel map

, and this solution is induced by an optimal transport map: i.e., there exists a Borel map  such that

such that

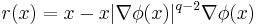

Moreover, if  has bounded support, then

has bounded support, then

for

for  -almost all

-almost all

for some locally Lipschitz, c-concave and maximal Kantorovich potential  . (Here

. (Here  denotes the Gâteaux derivative of

denotes the Gâteaux derivative of  .)

.)

See also

Media related to [//commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Transportation_theory Transportation theory] at Wikimedia Commons

References

- ^ G. Monge. Mémoire sur la théorie des déblais et des remblais. Histoire de l’Académie Royale des Sciences de Paris, avec les Mémoires de Mathématique et de Physique pour la même année, pages 666–704, 1781.

- ^ Schrijver, Alexander, Combinatorial Optimization, Berlin ; New York : Springer, 2003. ISBN 3540443894. Cf. p.362

- ^ Ivor Grattan-Guinness, Ivor, Companion encyclopedia of the history and philosophy of the mathematical sciences, Volume 1, JHU Press, 2003. Cf. p.831

- ^ L. Kantorovich. On the translocation of masses. C.R. (Doklady) Acad. Sci. URSS (N.S.), 37:199–201, 1942.

- ^ L. Ambrosio, N. Gigli & G. Savaré. Gradient Flows in Metric Spaces and in the Space of Probability Measures. Lectures in Mathematics ETH Zürich, Birkhäuser Verlag, Basel. (2005)